For these notes I have had access to the letters and journals of Fred, Emily and Mary Yates. They make fascinating reading, not only for their illumination of some lesser known patterns in the art of their day, but also as a window - especially in the case of Mary’s writings, into a unique vision and life, centered in the English Lake District in the early years of the last Century. These extracts are from their own writings, and other sources. They are arranged as far as possible, in order to let them tell the story in their own words. Apart from a few short biographical entries and citations, little yet has been published about Fred Yates. John Hodkinson, Hart Head Cottage, Easter 2002.

The simple chronology known is as follows:

He was born in 1854, in Southampton and lived for a while in Liverpool. Around 1881, he went with his parents to America, becoming a professional artist shortly afterwards. He had two periods of study in Paris, with Leon Joseph Florentin Bonatt, 1833 – 1922, a well known portrait and historical painter. Also, with Adolph William Bouguereau, 1825 – 1905, a painter with a similarity of spirit to the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, and known for pictures on themes from classical mythology, the Bible, and contemporary life.

Returning to the USA, he married on the last day of 1887, Emily Powers Chapman, a pianist and teacher whom he met whilst teaching in San Raphael, California. From 1890, they made their home in England, and their daughter Mary was born in 1891 in Chislehurst.

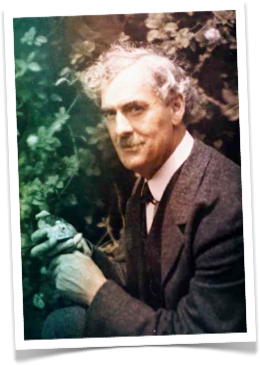

Fred Yates in an original

Autochrome photograph

After travelling in America, Japan and the far east, he began showing at the Royal Academy, eventually showing twenty works. Also at the Pastel Society, the New English Art Club, the New Gallery, and the Walker Gallery.

Following a commission to paint Charlotte Mason, the founder of the Parents National Educational Union, at Ambleside, he settled in the Lake District in 1902. Portrait work continued in his London studio, and on further visits to the USA.

He was a founder member of the Lake Artists Society in 1904. Squire Le Fleming built their house in Rydal, on a site picked by Fred and Mary.

Fred Yates’ other sitters include Sir Henry Wood and Woodrow Wilson, whom he met on Pelter Bridge. He became a firm friend of Wilson and was later a guest at The White House on Wilson’s inauguration as President. He died in 1919.

Mary, his daughter was also a talented artist. She later exhibited at the Royal Academy, and the Royal Scottish Academy between 1918 and 1924, and was a regular exhibitor at the Pastel Society, and the Lake Artists Society, and lived on in Rydal until her death in 1974. A large exhibition of his work was held at the Abbot Hall Art Gallery, Kendal, in 1975, along with that of his daughter, Mary Yates.

Beyond this bald chronology, Fred Yates was clearly a likeable and charismatic personality, which must have been a great asset in his career as a portrait painter. In the 1870’s and 1880’s the painting of portraits was a very competitive business with many artists at work in this field.

The arrival of the photograph had not yet had an impact upon the necessity of the painted or drawn portrait as an essential credential of the social elite. Yates’ background with Bonatt and Bouguereau clearly underpinned his skills, and his many portraits, in oils and pastels, show this. They are skilled and well-crafted likenesses, but the best of them bear real insight into the character and personality of the sitter. His obituary in the Times refers to his interest in this aspect of the portrait.

There is more to Fred Yates though, than the successful portrait painter. He also painted many landscapes and was very much a man of his times. His other interests in painting reflect the currents that were flowing through contemporary art in these times. He had a particular interest in the paintings of the Barbizon School and especially in Jean Francois Millet (1814 – 1875), and lectured widely on this artist. These painters of the Barbizon School were the early stirrings of the ideas and attitudes, which lead through Impressionism and on to painting in the 20th Century. All too often we tend to divide painting coldly, into discrete chunks, labelled by movements like crude university modules, rather than seeing it as the continuum which it really is, driven above all by people and their relationships.

In this respect, Fred Yates is in an interesting position. In training and professional life, he links with the academic traditions of the century, the Salon, the Royal Academy, and with the patterns of change. He also shares in the social concerns, technical innovations and shifts in ideas and values, which overlapped and led through from the painters of the Barbizon with whom he had been aquainted as a student, through to Impressionism and beyond.

Another artist, twenty years Yates senior, and also with American connections and who has tended to be seen as outside the definable movements, was James McNeil Whistler. He straddled the academic tradition and the changing currents of the time, embracing the aesthetics of Japan. He declared an ‘Art for Art’s sake’, forming a link between Victorian narrative, and painting in a modern context, abstract arrangements of form and colour, a painting which could leave simple description behind and explore states of mind.

In France, the politics of painting were sharply dividing. In the ‘comic book history of art’, seen panel by panel as it were, the uncompromising conservatism of the Salon eventually led to the breakaway of the Salon de Refuses in 1863, and then on to Impressionism, Post Impressionism, Cubism and the rest of modern art.

In The Hague though, these divisions were not so deeply etched. By 1870 it had become a centre for a group of younger painters, who shared much of the attitudes of the painters of the Barbizon, but who did not have the same problems of rejection as had the French painters of the Salon de Refuses.

This Barbizon influenced art had been popularised in The Hague by a branch of the Paris dealer Goupil, and by the dealer H. J. Van Wisselingh. Prominent among this group of painters were the brothers Jacob and Matthijs Maris. Matthijs Maris (1838 – 1917) was a quiet man who gradually moved towards a visionary and dreamlike quality in his painting. He settled in London in 1872.

One of his few friends was Craibe Angus, an English dealer who set up in Glasgow in 1874 and introduced this work of the Hague School to Scotland where it became very popular. William Burrell was an early collector of Maris’ work, (over fifty works.) In turn, this work became an important influence on the Glasgow Boys in the early years of the 20th Century.

In 1887, the daughter of Craibe Angus married E. J. Van Wisselingh (the son of H. J. Van Wisselingh,) who ran a London gallery. He, in turn eventually represented Fred Yates. Matthijs Maris became a good friend also of Fred Yates. Despite the popularity of his work, Matthijs Maris ended up in reduced circumstances, and was cared for by Mrs Van Wisselingh (nee’ Angus) until his death in 1907.

Such artistic ‘trade routes’ can be seen in a glance at other well-known British painters of the period. Sir George Clausen, two years older than Fred Yates also travelled in the Low Countries, and worked under Bouguereau. He once was described in his early years as “a very clever Dutch painter.” He was an admirer of Bastien-Lepage and was a founding member of the New English Art Club, itself a response to the conservatism of the Royal Academy. He has been described as a kind of ‘English impressionist”. W. R. Sickert, six years younger than Yates, attached himself to Whistler as apprentice and etching assistant. He met Degas in 1883 and subsequently became a close friend. He is another painter who does not easily fit into a neat category, but he remained connected to a form of impressionist point of view. Subsequent ‘trade winds’ are perhaps beyond the scope of these short notes.

A glance at Fred Yates work demonstrates the traces of these winds, which cover the continents as clearly as his work. We see skilful technique and the legacy of tradition. We also see vigour and broadness of handling paint, a relish for handling the “luscious stuff”, as Fred once put it, the way it wrinkles and smears. Paintings first need to be experienced the way a painter does, close up, from the inside. Let the subject go, engage with the paint, the marks. The generosity of spirit and the one-ness with the work necessary to the maker come in this way. To feel this is, I believe, to feel something of the point of view of the artist, and in this case, Fred Yates in particular, who believed in a sensual and essentially physical approach to the handling of paint, and the importance of allowing feelings and emotion to drive the act of painting as much as intellect and psychological insight. Content can come afterwards, with reflection – and eventually, contentment.

“I hope you will go on working – just as your finest self dictates, but everlastingly experimental, throwing out your energy like a volcano throws out fire, and again throwing out your love like a bird singing.” (From a letter from Fred Yates to Mary Yates, dated 25th November 1912.)

From notes for an the Exhibition at the Armitt Museum, Ambleside, November 2001 to February 2002. John Hodkinson, Hart Head Cottage, September, 2002